With increasing regularity, I have been hearing accusations that Bitcoin proponents are engaging in “greenwash”. Here’s why we need to be careful and considered in using this term.

Firstly, I have empathy for the user of the term. We live in a world where corporates frequently use greenwash as a strategy to cast attention away from their devastating environmental impact.

The first and most objectionable example of this was BP gas-stations using solar panels on their roofs. The issue wasn’t this in itself, but that they trumpeted this in so much of their marketing material as a reason for them making strides in a green direction.

In reality, each day, they were responsible for the extraction of oil which had the potential to produce millions of tonnes of Carbon-emissions. Solar panels on 1000 gas-station would mitigate <0.001% of their daily emission contributions. Greenwash.

When I first heard of Bitcoin’s environmental impact, as an environmentalist I was horrified. A friend in the Bitcoin ecosystem said that I should look at both sides of the story before casting judgement and directed me to a video of Andreas Antonopolous, who discussed convincingly how Bitcoin was uniquely suited to incentivize renewable energy by being a customer for stranded energy that other industry could not use due to being produced at the wrong time of day, or the wrong part of the country. Therefore he argued it made the renewable operator more profitable, and they would typically use that profit to expand their renewable operations.

Hmm – I thought. “Maybe – but maybe that’s greenwash”. I wasn’t sure. It was clearly better than a “solar panel on the roof of a super-emitter” but how much better? I didn’t know, because the case was not quantified.

Therein lies the problem. Much of the positive environmental externalities of Bitcoin are only now being quantified. Added to that, much of the early research into Bitcoin as mis-quantified, such as the now infamous Mora et al study that made a unit error resulting in a calculation that was out by a factor of 1000. Yet the study still made it into Nature magazine, had a widespread impact on seeding fear in the environmental community (it was cited at the start of GreenpeaceUSAs change the code campaign), and as recently as Oct 2023 was cited in a UN University Study on Bitcoin. The paper’s conclusions, though provably false, informed the world-view of the first wave of environmental antagonists of Bitcoin. Indeed it was the only paper cited in a letter of 70 environmental organizations to Congress opposing Bitcoin mining in October 2021.

There is also a risk that in an age where greenwash is prevalent, we as environmentalists may identify “false positives”. In other words, we prematurely evaluate an emergent technology such as Bitcoin as engaging in Greenwash, whereas the proponents may in fact be pointing out legitimate, quantifiable and significant benefits. In other words, there is a risk that “greenwash” can be used as a slur, an emotional response that prevents us legitimate objective evaluation. There is already evidence of opponents of Bitcoin using the term this way. For example, in a recent op-ed in The Hill, rather than engaging with the content on a recent KPMG report on the ESG Case for Bitcoin, the op-ed author labelled it “greenwash” because “KPMG has corporate holdings of Bitcoin and a business unit dedicated to crypto and

blockchain.”

Is this not an ad hominem argument however? The direct claim is that KPMG have a vested interest in the success of Bitcoin, therefore are greenwashing the technology. However, this is unscientific. Using this logic we could argue that we should distrust the recommendations of every Doctor, because they have a “vested economic interest” in telling us we are sick and prescribing us medication. We would all have to consult only physiotherapists instead. Afterall, its just a body, and physiotherapists know about the body too, but don’t have the vested interest of the Doctor. Similarly, we should not using this logic trust the professional opinions of Dentists, who have a “vested economic interest” in telling us our teeth need attention, and selling us amalgams. We should instead consult a general osteopath. Afterall – the tooth is just a bone, and osteopaths know about bones, but don’t have the vested economic interest of the Dentist.

This argument will not do. The very people we should be consulting are people who have a deep knowledge of grids, bitcoin mining economics and cryptocurrency, specifically Bitcoin. The fact that KPMG have a cryptocurrency division makes them more qualified to write the report. For one thing, there is less likelihood that they, through lack of knowledge of mining dynamics, make a 1000x unit transposition error.

We should of course have this information disclosed transparently, which they do, then adjudge their reports and others on the merits of their arguments.

Further, in such a case when evaluating any novel technology, should not the “innocent until proven guilty principle prevail?” Should we adjudge a technology having only examined its reported negative externalities, without either examining the accuracy of that reporting or the extent to which it also had positive externalities?

At what point does a positive externality become significant enough? Should we say that a technology is worthy of us withdrawing our criticism and calls for banning it only when for example it offsets more emissions than it produces?

Were this the metric then not a single technology on earth would escape our criticism or our ban.

Is it enough that a technology is making efforts to offset its emissions? And what speed of progress is important here?

These questions are important, because they reduce the risk of emotion-based decisions, and increase the likelihood of proper evaluation.

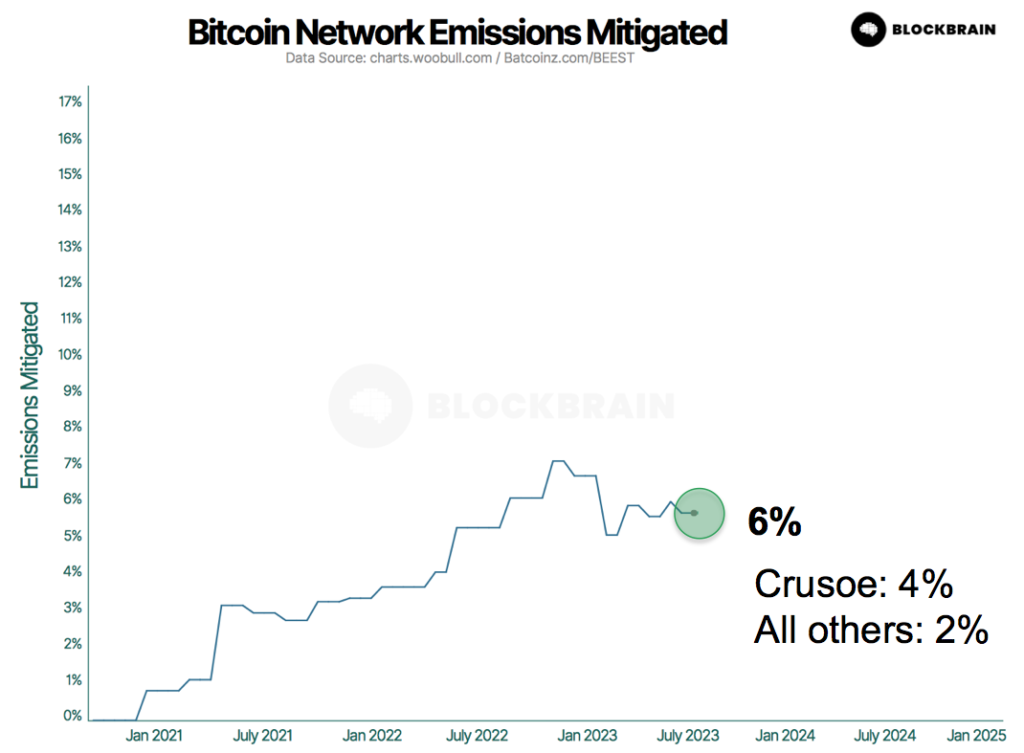

Bitcoin, for what it’s worth, currently mitigates an estimated 6% of its emissions through flare-gas powered Bitcoin mining.

Source: Blockbrain, BEEST, Quantifying the Emission Negative Portion of the Bitcoin Network

The Bitcoin industry has achieved this figure without buying offsets (a fraught process which has recently itself come in for the accusation of greenwash).

No other industry has achieved this figure without purchasing offsets. Is the fact that Bitcoin has achieved this in a matter of years, without the greenwash-accused method of purchasing forest-based carbon credits not something worthy of recognition?

So is an industry that has achieved 6% emission mitigation organically, at twice the speed of the solar industry, attempting greenwash? Or might this may be a legitimate positive externality that will increase further over time, as it did for the solar industry, and which warrants proper investigation.

It may be worth us remembering that the photovoltaic industry was invented in 1954, and produced vast swathes of emissions for the next 40 years via coal furnaces that melted the silicon required for the panels, until it was mitigating around 6% of its emissions. It eventually paid off its carbon debt in 2011 according to Nature Communications, 57 years after invention.

Is the fact that Bitcoin has achieved 6% emission mitigation of annual CO2e emissions within 13 years not worthy of recognition, or at least further investigation (genuine investigation? Should this investigation not be objective, not the confirmation-biased based faux-investigation from one who has prematurely evaluated that Bitcoin mining proponent claims must be greenwash, because they contradict one’s existing world-view?

2023 heralded a year where independent reports, peer-reviewed studies and mainstream media reports all pointed to the existence of meaningful and quantifiable environmental benefits to Bitcoin mining.

Should this not be pause for us to re-evaluate how we evaluate Bitcoin, based on the following approach (which really is nothing else other than the application of the scientific method)? ie:

- objectively,

- taking into account and quantifying both positive and negative environmental externalities

- challenging data-assumptions and models for both positive and negative externalities

- defining a full set of both positive and negative externalities

- seeking genuine expert input on each from people who understand the variety of domains necessary to offer insight (grid dynamics, demand response, bitcoin mining economics, methane mitigation, LFG powergen, battery engineering, renewable deployment and engineering)

Conclusion

It is important that environmentalists continue to test industry claims of environmental benefit robustly. There are dangers of assuming an industry claim is true without adequate objective research. However as we have shown, there are equal dangers in assuming a claim to be false without adequate objective research. Merely claiming a vested interest is an intellectually lazy, and invalid ad hominum argument, not evidence-based research. There is also a risk that through overuse of the “greenwash” accusation without adequate research, the term itself loses its currency and hampers the environmental movements attempts to point the finger at genuine greenwash. We would urge GreenpeaceUSA and the other 69 environmental organizations who signed an letter to Congress against Bitcoin citing falsified research (Mora et al) to look into Bitcoin more objectively and deeply than past assumptions, lest they become “the boy who cried wolf”, making it harder for the environmental movement’s claims to be taken seriously.